Before I learn a new software or new skills, I often like to do some homework and ask the silly questions like: what, when, why, and how, to give me a base understanding of the software. So, let’s work through these questions for R.

What is R?

R is a system that is used for statistical computation and graphics. It has a number of aspects to is that include a programming language, graphics, interfaces or connection opportunities with other languages, and debugging capabilities. I have found that many do not refer to R as a statistical software package, because it can do so much more.

What does this all mean? It means that R is a very robust program that folks use for a variety of reasons, it’s not just for statistical analysis!

Where did R come from?

The history of software packages can be quite interesting to learn about. For instance R has been defined as a “dialect” of S. Some of you may remember the statistical software called S-Plus? Well, that’s where R comes from. It was developed in the 1980s and has been one of the fastest growing open-source software packages since.

What does “open-source” mean?

I’m sure you’ve heard of this term in the past or in different contexts. One thing that you will hear when people talk about R, is that it is free or that is is open-source. Keep in mind that open-source means that it is freely available for people to use, modify, and redistribute. Which usually translates to: there is no cost to acquire and use the R software! Another aspect of open-source is that it is or rather can be community-driven. So, any and all modifications to the software and subsequent documentation (if it exists) is driven by the community.

Please note, that R has matured over the years, and today’s R community is extremely strong, and encouraging documentation for anything that is released, making it a very desirable product. This may not always be the case with open-source software.

Who uses R?

Business, academia, statisticians, data miners, students, and the list goes on. Maybe we should ask the question, who is NOT using R, and then ask the question Why?

There are so many different statistical software options today and which one you choose to use will depend on several different factors:

- What does your field of study use?

- If you are a graduate student, what does your supervisor suggest and use?

- What type of analyses are you looking to perform and does your program of choice offer those analyses?

- What types of support do you have access to?

How does R work?

If you’re looking for a statistical package that is point and click, R is not for you! R is driven by coding. YES! you will have to learn how to write syntax in R. You can use R interactively by using R-Studio, and you may never reach a point in your studies or your research where you will move away from the interactive capabilities of R – so no big worries! Besides, today there are a lot of resources available to help you learn how to use R. So don’t let that stop you!

Base R and Packages

When you download and install R, the Base R program is installed. To run many of the analyses you may be required to install a package. What is a package? It is a collection of functions, data, and documentation that extend the current capabilities of the Base R program. These are what makes R so versatile! As we work through our workshops and associated code, I will provide you with the name of the Package. There are a number of ways to acquire and install packages, we will review these as we work through them. Please note that there may be several packages that perform a similar analysis, please read all the documentation before selecting a package to use.

How do I acquire R? Where can I download it?

Visit the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) website to download the R software. https://cran.r-project.org/ Please note that this will also be the website used to download future packages used in analyses as well.

The website has comprehensive instructions to assist you with the installation on your own computers.

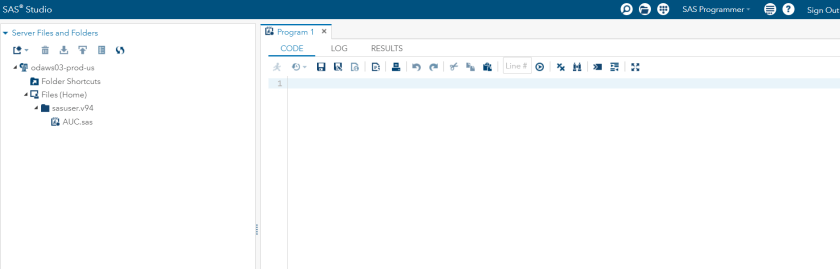

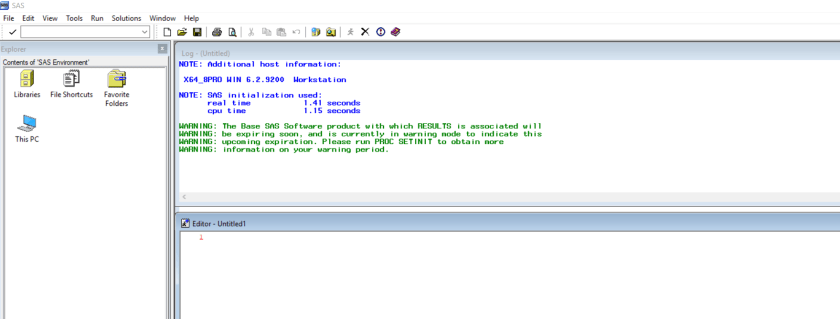

Available interfaces for using R

There are essentially two ways to use or interact with R: RStudio or by using the R Console. The code or syntax you will write or use will be the same for either interface, however RStudio provides you with a more interactive experience. This is the interface that I will use for these workshops. I will demonstrate the R Console to show you the basic differences.

In order to use RStudio, you will need to download and install it once you have R on your computer. To download R-Studio, visit The RStudio website at https://www.rstudio.com/

Let’s take a tour and become familiar with the windows in RStudio

When you first open RStudio you’ll see 4 windows or 4 sections on your screen: editor, console, history, and environments with tabs. Let’s start with the environments window – you should see 6 tabs: Environment, Files, Plots, Packages, Help, and Viewer. The Environment tab lists the files/datasets that are being used during the current project. The Files tab allows you to view all the files that are available in your working directory. The Plots tab will show any plots that are created during your session. The Packages tab will list all packages that you have loaded. The Help tab is self-explanatory. A quick sidenote, the Help window is great! Please take advantage of it by using the search function in the Help tab.

The History window will list all the lines of code that you have run until you clear it out. A great way to see what you have done – especially if you encounter troubles along the way.

That leaves the editor and the console. The editor is where you open an R script file and the console is where you run your code as you type it in. To run code that is in your editor – select the bits of code and hit Ctrl-Enter to run it. In the console, you type the line, hit enter and it runs immediately. I use these two windows in tandem. To move between these two windows – Ctrl-2 moves you to the Console window and Ctrl-1 brings you back to the editor window. Of course, a mouse works great too!

One more quick tip – the console window can fill up quite quickly and to me, can feel very cluttered. Remember the History window will keep a history of your code, so it would be ok to clear out the console as you see fit. In order to do this, use Ctrl-L to clear it out.

Working Directory

Sometimes having your program always refer to the same directory, when saving files or when opening files, can be very handy. You’ll always know where your files are! R makes it very easy to accomplish it.

First, let’s do it the long way. To see what the current working directory of your RStudio is by typing in your editor window:

getwd()

To change the working directory for the current project you are working on type:

setwd (“C:/Users/edwardsm/Documents/Workshops/R”)

Of course, you’ll want to make this a directory on your computer 😉 But as you look at this – do you notice anything odd about this statement??? You’ll notice that the slashes / are the opposite direction than you normally see on a Windows machine. Changing these manually can be a time consuming effort. One way around this is to add an extra \ after everyone in your location. See below:

setwd (“C:\\Users\\edwardsm\\Documents\\Workshops\\R”)

Always double-check your working directory by checking getwd() Are the results what you were expecting? If not, try it again.

There are easier ways to accomplish this as well:

- In RStudio, Session in the File Menu provides 3 options for setting your working directory:

- To Source File location (the directory where you save your R script and program files). If you try this when you first open RStudio you will get a message that says: “The currently active source file is not saved so doesn’t have a directory to change into.” In other words you haven’t opened any files yet, so R has NO idea where it is working from. This option works only after you have opened a file.

- To Files Pane Location – in the Files Pane – navigate to the location you want to have as your Working Directory. Once you have it selected in the Files Pane, then choose Session -> Set Working Directory -> Files Pane location. You will see the new working directory appear in your console and it should match what you select in the Files Pane.

- Choose Directory – will open a windows dialogue box where you navigate and select the directory of choice. This option is probably the best option once you have opened RStudio and have not opened a file.

- While you are in the Files Pane location – navigate to the directory that you would like to set as your working directory, then in the Files Pane – select More -> Set Working Directory. This option is very similar to the Files Pane Location option under the Session menu of RStudio.

As a best practice, when you are working with R – set your working directory once you open the program.

R packages

As mentioned earlier, R is made up of a number of packages. Remember that a package is a collection of functions, data, and documentation on a specific topic or analysis. There are 2 types of packages: standard packages – those that came with your Base R OR a package that you downloaded from CRAN or elsewhere.

To view a complete list of R packages available on CRAN, please visit https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/available_packages_by_name.html

Once you download a package of interest, you need to install it and load it before the functions within are available to you in the R environment.

There are a couple of ways, that I am aware of – at the moment, of downloading and installing new packages:

- 1. From the RStudio file menu, select Tools, then select Install Package

Notice that the default is to search for the package on the CRAN website

If you are using this method – please ensure that the Install dependencies box is selected.

- 2. Typing a command in the Editor window

install.package(“packagename”)

You will notice that with either method that use, in your RStudio Console – there will be a series of operations that occur during the installation.

Once you have the package installed, you will still need to load the package in order to let R know that you are ready to use the functions within the package. Without loading the package, R will not be aware of the package or of the functions you may be trying to use within a package. To load a package please type:

library(packagename)

As we work through the workshop, I will try to have the packages we are using listed at the top of each R script we will be using. I will ask you to install the package and then load it to make it available for your session.

Keyboard Shortcuts

For anyone who relies more on their keyboard than their mouse, here are a few keyboard shortcuts that may be helpful.

Keyboard Shortcut Function

Ctrl-Enter Submit code

Ctrl-1 Move to Source window

Ctrl-2 Move to Console window

Ctrl-L Clear Console window

Alt – <-

Let’s Get Started with Reading Data

Now that we have R and RStudio installed on our computers, and we have a little background and history about R, let’s get started by learning how to read data into the R program.

Notes to Read Data into R are available as a PDF document. Please download and save on your laptop.

The session was recorded – but we had a fire alarm and then the recording didn’t work for the last part of the workshop. The links to the 2 recordings are here though.

Introduction to R – Reading data into R – September 17, 2019 (Part I – before the fire alarm)

Introduction to R – Reading data into R – September 17, 2019 (Part 2 – after the fire alarm – note that only part of the remaining workshop was recorded)